A Seat at the Window

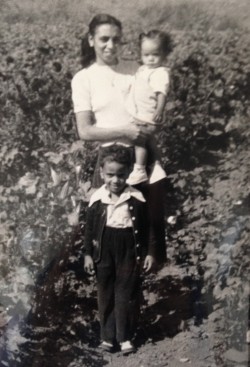

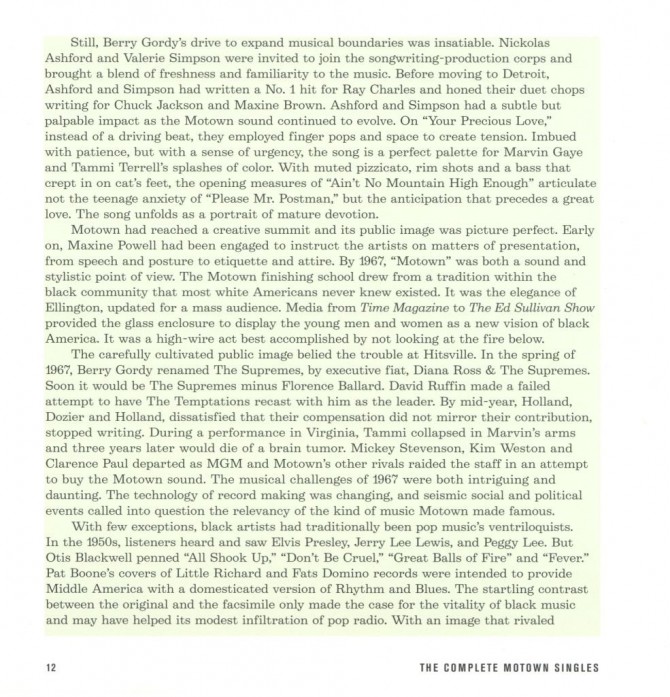

Left: the author’s mother, with siblings Jimmy and Margaret, in a cotton field;

right, the author and his “Pops” in Detroit.

Below, “Papu” at the Mercy Seat Baptist Church.

Detroit. June 1964.

The house is buzzing. Mom is packing the ice chest—ham sandwiches, cold fried chicken, cookies she just pulled from the oven.

“Seven days,” she calls out. “That’s how long we’ll be gone, so make sure you have everything you’ll need.”

This is not just any road trip; we’re going to Mississippi. Pop moved the family to Detroit when I was little. We go back every couple of years. Detroit to Greenville. It’s really two vacations in one. The car trip, and the week we spend down south.

The day we leave is exciting, in the same way as Christmas Eve. It’s funny how thinking about what’s about to happen can be as good as when it actually happens. I guess that’s true the other way, too—thinking about a bad thing before it happens is like living it twice. Mississippi is all over the news and none of it’s good. It seems like every day I hear “We interrupt this broadcast for a special report.” I try not to listen. For us, this is vacation.

There are certain things we can get away with today that Mom wouldn’t put up with at any other time. So me and Jimmy Jr. test our luck. The long hallway is perfect. I fire a pitch that bounces off the ceiling and the wall.

“Are you crazy? What was that?” Jimmy Jr. scoffs.

I was trying it with my left, like Sandy Koufax.

From the kitchen, there’s Mom, “Don’t make me come in there.”

We head to the back room. Out of sight. And we’ve got a radio. Everybody else has transistor radios, but we’ve got this thing that looks a hundred-years old. Who makes radios out of wood anymore? Who cares? It works. And they’re playing my jam. With the volume way down, we lean in, four heads bobbing, “Is it in his eyes? Oh No. You’ll be deceived.” When Betty Everett gets to the part “Oh No. That’s not the way. And you’re not lis-nin’ to all I say.” We jump up and form a line. We’re stepping, heads jutting in unison, singing Shoop, Shoop, Shoop, Shoop.

Then we hear the car pull into the driveway.

“Pop’s home!” We’re out the door and headed for the car. We run past Pop like he’s invisible, and scramble to claim a spot in the back seat. It’s furious. Once you have your spot no one can take it from you. That’s the rule. And you can only claim it by planting your behind on the seat.

Margaret and Jimmy Jr. are older, bigger and faster, so I’m stuck in the middle, the spot with the hump in the floor. Stuck in the middle seems to be what being ten is about. It’s worse for my little brother Bruce who just squeezes in wherever he can. Marsha, the youngest, sits up front. All of that scrambling for nothing. Can’t worry about it now. Got to finish packing.

Twenty-four hours is a long time to be trapped in the back seat with those guys. I know at some point I’ve got to make a deal. Better grab something I can use to trade up. Okay. Got It! I grab A Rocket to Luna. Margaret is an easy touch for anything Sci-Fi. Aliens, robots. What do I care? But she loves it. I know this book will get me the window.

Even though Margaret is only three years older, she thinks she’s my personal boss. “Are you all packed? You know you always forget something,” she yells.

I don’t need much, just my Converse All Stars, a couple pair of shorts and a shirt or two—and, of course, my baseball glove. I stuff the glove in my duffle bag and holler back, “Don’t worry about me! What we need is a song list. This time, the top 20 countdown. The one from—”and I sing the jingle—“CKLW.”

We always take songs off the radio and television and give them the words they should have had. Last trip we’d just seen Peter Pan, so it was easy. When one of us would get car sick, instead of “I Won’t Grow Up” we’d sing “I Won’t Throw Up.” Instead of “I’ve Got to Crow” we’d let Pops know that we had to pee by singing “I’ve Gotta Go.” And after too many hours on the road Jimmy Jr., who could fake drama better than any of us, turned “I’m Flying” into “I’m Dying.” There’s a joke in every song and it’s up to us to find it.

We leave right after Pops gets off of work—all seven of us in a white 1961 Pontiac Catalina. The trip’s gonna be long, and Pops wants to get down the road before nightfall. The three of us—Margaret, Jimmy Jr. and me—the ones born in Mississippi, know the route by heart. We can name the towns—Indianapolis, Cairo, Paducah, and Memphis. We’ll teach the two little guys the towns and everything else about a road trip.

In Detroit we build cars, and we really know how to drive ‘em. Pops behind the wheel of the Catalina is not to be missed. It’s not long before we’re stuck behind some slow-driving farmer on a two-lane highway. It’ll take us forever if we don’t find a way to get around them. One good thing about the middle seat is you have a clear shot out the front windshield. I lock in like a back seat co-pilot as Pops looks for an opening in the oncoming traffic. Bam! He jams the pedal to the floor. That Pontiac jumps into action and we swing into the other lane.

When I look over Pops’ shoulder there’s a car headed straight at us. It looks small and way off at first, and then, just like that, they’re right up on us. There’s no way we’re going to get past that slowpoke and back into our lane in time. Somehow, Pops always gets it just right. Yeah, I close my eyes at the last second. But I never really doubt Pops.

Those old Peter Pan songs are okay, but it’s time for something new I pull out the list. “You know that song by The Contours’ ‘Do It’ ? It goes, ‘It’s 1964 and we gon’ dance some mo.’ That’s the one.”

As always, my boss puts me in check: “Do It? Well, you better not let Mom and Pop hear you singing that.” Margaret whispers her version of Mom. “Your grandfather, Rev. L.J. Jordan, is the pastor of Mercy Seat Missionary Baptist Church in Greenville, Mississippi. The Jordans do not sing the devil’s music.”

I whisper back. “Well, I am not Rev. Jordan and I like the devil’s music. So, we’ll sing low—like we do.”

Not long after we hit the road we huddle in the back. To the beat of a finger snap, we do our versions of hits by Little Stevie Wonder, Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons and Martha and The Vandellas. Some songs, like Major Lance’s “Um, Um, Um, Um, Um, Um” we can sing out loud because they aren’t that different from kid songs. “Everybody Say Yeah!” By the time we roll past Cairo we’ve run the list, except for The Beatles. Margaret starts in. “She was just seventeen. You know what I mean . . .” Me and Jimmy shut it down. “And the way she looked was way beyond RE-PAIR.” We mock the John and Paul’s head shake and dismiss ‘em with a Yeah, Yeah, Yeah.

Pops had worked a full day before we set out on our trip. So, we know that at some point he’s going to need a nap. The gravel kicks up as we coast to a stop on the shoulder of the road. I’m the one who always asks, “Why Not!” And I want to know, “Why don’t we stay in a motel?”

My mother just says, “Your father has his mind made up.” I wasn’t about to bother him, but he heard us. “I just need a nap—couple of hours. This is a good spot.”

Mom takes over. “Now you all be quiet, your father needs his rest.“

I give in. Fine, I’m thinking. At least it’s a chance to raid the ice chest. Cold fried chicken makes you wonder why people eat it any other way.

Pops can nap, but not me. The stars are really bright and I’m way too excited.

By tomorrow we’ll be there. Mississippi is Bug Heaven and I’m the Bug Man. First thing, I’m headed straight to the high grass where the giant black and yellow spiders, the dragonflies and the grasshoppers live. I know ‘em all. I’m going to ditch brothers, sisters and cousins. It’s just me and the bees. I know bees, too. I can tell you if it’s a bumblebee or a honeybee just by listening to the hum.

In Mississippi the trees have leaves and flowers. Something called a Mimosa tree, and another they say is a Magnolia. Butterflies—tiger swallowtails, red admirals and monarchs—love those flowering trees. Someday, when I’m a scientist, I’ll know what they’re thinking.

My grandparents Mamoo and Papu’s backyard: Big pecan trees. A woodshed full of mysterious stuff. Chickens all over the place. A gang of cousins around the corner. Swim every day. Pops going heads-up with his brothers at basketball. Going down to the levee. The guy walking a cart down Alexander Street hollering “Hot Tamales!”

“Wake up, Herb!”

Bleary-eyed. I push Bruce off. “Huh? I wasn’t sleeping. I was just watching the stars until Pop woke up.”

Before we start our morning drive, the brothers Jordan disappear into the bush. “Good,” Jimmy Jr. says. “No girls to tell you to put the toilet seat down, or don’t pee all over the bathroom.”

Out here you get to aim it wherever you like. Nobody to stop you when you point it up and watch it come down like a rainbow. Jimmy Jr. awards extra points for blasting an insect off of a branch. The three of us unzip and spray everything in sight. Man, I can tell, this is going to be a great trip.

It’s different for girls, though. Mom walks into the bush like the ladies on Ed Sullivan walk onto the stage. Don’t know how she does it, but her dress looks just as neat now as when we left Detroit. She always carries the white chamber pot so that you barely notice it. But I notice. And I notice that she comes out of the bushes the same way—walking like somebody was about to hand her a statue.

Back at the car I ask, “Why do we have to comb our hair on vacation? If you want my hair combed, you’re just going to have to catch me.”

Mom never falls for it and just does a pretend schoolteacher. “Do as you like, but only those with hair, properly combed, will be served breakfast.” Just like that, five well-groomed kids in a chow line waiting for Mom to pass out sandwiches from the trunk of the car.

And then, we’re back on the road.

We’re making good time. By mid-day we’re in Kentucky. Horse country. Margaret’s reading Rocket to Luna.I’ve got my window seat. We know horses from my uncle Herb’s farm up in Canada. Up close, horses are huge and kind of scary if you stand too near to them. Here, it’s like a painting. The grass is a green carpet lined by white rail fences. The barns are neat and painted, mostly white, sometimes with blue trim. Once in a while you see a red or even black barn. They rise up out of the road as the Pontiac glides around the curves. Together the Backseat Four raise our hands and announce “Mail Pouch Tobacco,” when we come upon a barn with those words painted on the side. I wish I could slow time.

We stop singing and watch the road wind over the low hills and the horses grazing beyond the white rail fences. It goes on for miles, but it’s over too soon. We’re on to Tennessee.

He would never admit it, but Pops doesn’t like to stop for anything except gas. The minute we spot the big yellow sign “Welcome to Stuckey’s. World’s Finest Pecan Candies,” we start in. “Pop. Don’t you want Stuckey’s?” It never works, but we always try. “There’s the Exit!” starts off loud and hopeful, and then trails off as we zip past.

Mom steps in. “We’re making good time, and your father wants to get to Greenville in time for dinner.”

A tank of gas gets us all the way into Brownsville, Tennessee. We roll into the Shell station with the needle on “E.” By now, I’ve really got to go. Me and Jimmy Jr., my other boss, look for the Men’s Room sign.

“Lose the glove,” he says. “You can’t take that into the bathroom. You think you’re Willie Mays.”

“Nah,” I say. “Sandy Koufax. That’s my man.”

As usual, Jimmy’s response comes with a headlock. “Stop dreaming, man.”

I push him off and we go into the bathroom laughing.

We come out arguing Mays verses Koufax. I stand my ground when it comes to Sandy Koufax. I stop, stare at the catcher and nod my head. Fastball, high and outside. Jimmy’s all over me. “Don’t start that lefty stuff again!” It’s too late. I start my wind up and raise my leg for the high kick.

Out of nowhere the gas station attendant charges at us. “You little Niggers! What the hell you think you doin’? That’s a white restroom!” My heart stops. His voice is high-pitched, choppy and sounds like The South.

We freeze. We’re too far from the car to make a run for it. I look at Jimmy Jr. “Oh Shit! Here he comes.” All I can see is a grown man with wild eyes and a red face charging at us.

Then, the thunderbolt from across the way: “If you take one more step towards those boys!”

Me and Jimmy Jr. know that voice. We know the gas guy is in big trouble. He must know it, too, because he stops dead in his tracks. His face has changed; now it’s half mad and half scared to death. There’s Pops, standing there, same as he looked in those army pictures from the Philippines. Ready.

To look at Pop you’d think he plays cornerback for the Detroit Lions. But really, he’s a peaceful man, except he doesn’t put up with any kind of nonsense. I hope he didn’t hear me say “shit.”

Pop could have KO’ed the guy. Instead, he points at him. “You come over and take that nozzle out my car. Now! I’m not buying gas here.” I breathe out. Pop’s got it under control.

Pop doesn’t like to have to tell you to do something twice. That guy must have figured that out. I think he knows he’s better off doing as he’s told than to keep hollering at us. It’s straight-up fun to watch the guy, who looks like he’s shrunk to half his size, go over and take the nozzle out of the car. He has the same walk as when we get put on punishment. He starts to say something, but Pops gives him The Look. I guess The Look works on just about anybody, anywhere.

We can hardly contain ourselves as we climb back in the car. The back seat is jumping. I start it off. “Man, did you see that!”

Then Jimmy comes back with the high-pitched cackle, “You little Niggers . . .”

We crack up. “Yeah, Pop showed him!”

Mom cuts it short. “Keep it down back there. This is no time to celebrate.”

We quiet down a little, but we can’t be stopped. That was better than watching Gunsmoke.

Pop, like nothing at all has happened, says, “Well, I guess we’re going to need some gas.”

He spots a service station down the road and pulls in. This time, we stay in the car. The attendant, this big tobacco-chewing white man, walks straight up to Pops and in a gravely voice says, “I knew you were coming.” Maybe Mom is right. This isn’t very funny.

The cackling man had called to tell him that we were headed his way. Okay. This isn’t looking good at all.

But this guy is different. He gasses us up and then nods at the car full of Northern Negroes. “Enjoy your trip.”

Pops looks calm as always, but we pull back on the highway and shoot through those Tennessee hills like lightning. He keeps an eye on the rearview mirror.

It isn’t long before it starts to rain. Driving through rain always feels good—at least from the back seat. It’s coming down so hard we can’t see. But you can hear. I’m just breathing, listening to the sound of tires on the pavement. The Catalina’s big engine is working and the windshield wipers keep time, Fa lap a doop, Fa lap a doop. The rain is like tiny snare drums, beating on the car roof. A couple of miles of those wipers and I start my own Fa lap a doop. I shoot Jimmy Jr. a look. He picks up the beat. There it is. The Backseat Four have another song. We start to work it. Everybody’s got their part. Then Mom leans into the back seat, “Not now.” Then quietly so we couldn’t hear—but I did—she says, “Jim, you know we have Michigan plates.”

Mom grew up in Canada. She isn’t used to this kind of foolishness. We had heard stories about how Mom’s side of the family left The South a long time ago. I used to think it was this road trip, a journey, kind of like the way people came to America. I wonder. Were they running from America? Were they moving fast, looking back over their shoulders all the way to Canada?

After all of that, here was Mom, back down south.

We all relaxed when we saw signs for Memphis. At last, tall buildings, four lane highways full of cars. Almost normal.

Memphis is the last city before you hit The Delta. To get to Greenville you’ve got to go past Tunica, Clarksdale, Cleveland and Alligator, the last names on our list of towns. It doesn’t seem like they have actual cities in Mississippi. Just little places with cool names like Midnight. “Hey! Wake up,” I said. “I made a song out of these towns.” I call out the beat. “Ita Bena, Mound Bayou, Indianola, Sugar Ditch, Rolling Fork.” Everybody is tired. Jokes that would have cracked us up in Illinois don’t cut it now.

Even if we can’t muster up a song, I make sure everybody is wide awake when we hit the Mississippi state line. “If you guys don’t pay attention to anything else on this trip, heads up. You’ve got to see this.”

Down Highway 61, we watch men chained together in striped uniforms working on the roads. Then come the rows of what they call shotgun houses—grandmothers on porches looking after a gang of barefoot kids and the houses looking like the next gust of wind might blow them over. Looks like almost everybody in Mississippi is black. Well, except the guy with the shotgun watching over the chain gang.

And cotton. Good Lord! As far as you can see, rows of green and white, and black. Everybody knows that people in Detroit work hard. People in Mississippi work hard and it’s hot.

It’s the up-north-kid-can’t-walk-on-the-sidewalk-in-his-bare-feet hot. I tell Jimmy Jr., “I hope our cousins don’t remember when I took off my shoes and tried to walk on the sidewalk.” Margaret cracks up. “Ha. Remember it? They turned it into a dance. The Herbie Hot Foot. It was pretty cool, too. Kind of like doing ‘mashed potatoes’ on broken glass.” My big mouth. Shouldn’t have mentioned it. I know the minute we see them, Margaret and Jimmy will start that “Remember this” stuff, and break into the dance.

We roll on. Mississippi is its own kind of pretty. Not the Kentucky picture-postcard pretty, but flat, black dirt, rows-of-crops.

By this point, we’re mostly pushing each other’s hot sweaty limbs away. I still wonder where the side roads, more like trails, go. To even smaller towns, or deep into the woods, or do they just end in the middle of nowhere?

Pops likes the straight shot. I’m always glad to see detour signs. Detours take us deeper into the back country where you can see old graveyards with falling down headstones, ramshackle stores with hand-made signs and white wooden churches no bigger than a house. No chance Pops will check out the back roads for the fun of it.

It’s almost dark by the time we pull up to my grandparents’ house on Alexander Street. There’s a bunch of Jordans on the porch like they have been waiting all day for us to get there. Uncle Carl runs down the stairs with his big grin and checks out Mom and Pop, head to toe. “Look at you. Silk and steel. Detroit Style.” My cousin Jimmy Lamar circles the Catalina and whistles at it like it’s some girl walking down the street. The chrome picks up the sparkle from the streetlights and the flashing sign on the White Rose café next door. I inspect the Catalina’s front grill for unlucky bugs. They never knew what hit ‘em.

Night smells different in The Delta. The air is thick, and sticky, and sweet. I stick my tongue out and try to taste it. Cicadas, crickets, bullfrogs and their night creature friends start their racket the minute it gets dark. Sounds like they’re talking to each other, and to me. They don’t know they might end up in my collection.

Everybody’s crowded around us grabbing suitcases. Boy cousins start right in rough housing. Cousin Mollena sounds like a bird. “I’m glad ya’ll finally made it.” Then like a loud bird. “Cause I’m hon-gray.”

Down in Greenville they call Pops “James.” You can tell a lot about a person by the way people call their name. It’s “James this and James that, and remember when James . . .” I think they even named my cousin Jimmy Lamar after him.

Dinner’s ready. There are two tables for kids and one for adults with my gramps, Papu, at the head. The minute Papu looks up, the room quiets down. He asks, “Pretty car, James. You build it?” From the other end of the table Pops calls back, “Nah. I’m at Ford’s.” Aunt Leona goes “Ooooh-Yeah, Mustang. Mr. Grayson’s got one. Sharp.” Pops: “We turn em out, one-a-minute.” Uncle Carl can’t believe it. “You serious?” Pops has everybody’s attention.

“You ever see the episode where Lucy’s on the assembly line?” Bessie, from the kids’ table: “Oh, yeah, the one with the chocolates.” Everybody’s laughing at the thought of Lucy and Ethel, and the chocolates rolling past. Pops raises his voice up over the laughter. “Try that with a forty-pound bumper.” Uncle Carl: “Good way to break your back.” Pops: “Line never stops. If you take two extra steps to bolt on a bumper, you’ve got exactly two steps less for the next one.” Aunt Pazetta goes “Humph. Too much like choppin’ cotton.” The kids’ table’s on it. “Least they get paid.”

Uncle Carl looks at my mom and announces, “In your honor, Ilene, we are not serving chitlins.” Uncle Lawrence calls Mom out, “You all should have seen her when she first moved down here. She walked into Mamoo’s kitchen with this look on her face.” He exaggerates, high pitched and proper, “‘What have I gotten myself into?’ The girl held her nose and looked at that pot of chitlins with one eye open, ‘You actually eatthat?’ ”

Mom holds her own, speaking the Queen’s English. “Now. They look like intestines. And they smell like intestines. I wasn’t sure why you’d have them in a kitchen.” She’s got ‘em laughing. Pops shoots her a wink from across the table. “There was a whole lot about Mississippi I just didn’t understand. Still don’t. Can someone explain to me exactly what is a Mojo? And how do you know when it’s workin’?” My uncles look at each other and crack up. Uncle Carl: “All I can say is, “You know it when you see it.” Mom flashes that smile, “Well, we don’t have Mojo in Canada. Nor do we have chitlins.” Everybody’s laughing. Uncle Carl: “I think we just saw some Canadian Mojo.”

It’s Saturday night and Papu’s got to work on his sermon. So, we head to the cousins’ house. Uncle Lawrence lights up a cigar and everybody piles into the living room. You’d never know that eight kids live in this house. Everything is in place. Nobody is thinking about turning on a television. These guys can tell some stories. One thing I remember about Mississippi is loud. When it’s funny, people laugh loud. When they’re mad, you hear it, too. That night starts off with laughs.

There’s always a story about Nelson Street. Down on Nelson, they play the blues. Standing like she’s running for office, Mamoo leads off. “There’ll be no dancin’ in my house. I don’t believe in it. All that sweatin’ grindin’ gyratin’. Just ain’t right. Can’t dance with the devil on Saturday night and be right with the Lord on Sunday morning.”

Cousin Jimmy Lamar gets up, grabs Mamoo’s hand and tries to get her to dance. “Come on, now, Mama. A little wiggle never sent anybody to the devil.” Mamoo isn’t going for it. She just stands there and looks at him like he’s crazy. The air goes out of Jimmy Lamar’s dance moves and he lets go of her hand. Uncle Lawrence was next up. “You children listening? You can go one of two ways. Like your grandfather, the good Reverend. Or, he nods, like your cousin over there. I don’t want to see any of ya’ll end up like those people on Nelson Street, all that liquor and gamblin’. And loose women, too.”

I don’t think they’re making a very good case against Nelson Street. So I shoot cousin Bessie a look. She flashes a smile and waves her raised hand. “Let me tell you. On Nelson, they party ‘til the sun comes up!” Jimmy Lamar jumps in. “Or the cops come down. Either one.” Everybody laughs.

After a while they kick us out so the grownups can talk. Jimmy Lamar’s halfway between us kids and the grownups so he stays in the living room. It’s not loud and there’s not even a snicker. They must be talking about what happened at the gas station in Tennessee. I eavesdrop.

I could hear Uncle Carl. “Look, it’s a Jim Crow world.” Jimmy Lamar isn’t having it. “Jim Crow? What the hell does that even mean? They take funny sounding words and make it all so polite. Bodies swinging from trees, people vanish into swamps. Jim Crow? Segregation? Why don’t they just come out and call it what it is?”

Mamoo: “Watch your language, young man.” Uncle Carl pushes back. “So this young blood’s gonna change everything, even the way people talk. Is that what those freedom riders are filling your head with?” Jimmy Lamar stays on it. “Look-” Then, like he remembered he wasn’t grown yet, “No Sir. I’m trying to make a simple point. What you name something tells people how to think about it.” Aunt Pazetta smiles, “So, that girl, what’s her name? Shabuta Otis? She’s going to have a rough time of it.” They all laugh, but you can hear Aunt Pazetta above it all. I bet they could hear it all the way to Nelson Street.

Pops steps in. “Hey! Bring it down. The kids don’t need to hear all of this.” It’s back to quiet, but the last thing I hear is somebody say something about what happened to those “three boys over in Neshoba County.”

After that, Jimmy Lamar gets put out too. He flicks an “I’m through with this” hand at the living room, just out of their line of sight, and heads for the den where we’re already at it.

The cousins have no problem with loud. We have a week’s worth of stuff to figure out, and a year-full of news to catch up on. The only problem is when girls outnumber us. They only let me get the first half of my sentence out before they finish it. Then they just keep going with what they think I was going to say. It’s usually not.

This is vacation, so none of the grownups yell “bedtime!” We start to run out of gas after midnight and it’s time to claim our spot in the row of pallets on the living room floor.

But we can’t sleep. Jimmy Lamar nods toward us, and whispers, “I’ve actually been to Nelson Street.” Mollena and the girls rise up. “Stop lying.” Jimmy Lamar isn’t one to back out of a thing once he’s started. “Un huh. Crawled out the window one night to find out what all the fuss was about.” Mollena rolls her eyes and Bessie just closes hers and shakes her head. ”You expect us to believe this?” Jimmy Lamar gets serious, like this thing really happened. “I’m telling you. I slipped out and headed straight for Etta’s. Stood around outside a while to see what the story was.

The place was rockin’. You could hear laughin, shoutin’, Sister Luberta, Maybelle and Ba Bra. I knew I hadto get in. But, there was this Big Negro checkin’ people at the door. He didn’t ask for ID. He’d just look you up and down. It was like he could spot 17 a mile away.” Like sisters do, Mollena’s all over him. “If you had any sense you’d have brought your butt back home.” Jimmy Lamar’s not having it. “You know by now what kind of sense I have.”

He looks at us. “Want me to show you how I did it?” Bessie groans, “Do we have a choice?” Jimmy Lamar keeps it up. “So, the only way I’m getting’ in this joint is with The Walk.” Mollena, “The Walk? Come on.” She looks at the northern Jordans. “Here he goes.”

Jimmy Lamar jumps up. “Check it out.” Like he flicked some kind of switch, he starts stepping like a man. He makes like he’s taking a pack of cigarettes out of his shirt pocket, taps it on his wrist and pulls one out. He’s got us now. All eyes on Jimmy Lamar. He cocks his head to the side, makes like he’s nodding at the Big Negro, and walks straight through the door. “It’s all in how you do it.”

By now, we’re howling. There’s no stopping Jimmy Lamar.

“So, let me tell you how it is. Once you get in, there’s a piano player, name of Honeyboy. The place was packed. Everybody was there. The hot tamale man. That fine thing that works at the White Rose. They had corn liquor. Mr. Mellobelly’s Ribs. Dudes shooting crap in the corner.”

“And Man, you should have seen Sister Luberta. She had this thing going with the bass player. Every time he’d hit that low note, she’d shoot him a look and bump that ass. Bam! Right on the beat.” Bessie: “ooooh, you better stop.”

But he didn’t. “Just when it got good, Roy Lee Walker spotted me and they ran me out of there. Mamoo never knew, ‘cause, come Sunday, I was sittin’ in the first pew singing Precious Lord. Wasn’t just me. You know our choir director, Mr. Grayson? Over to Etta’s they call him Honeyboy.”

Bessie still laughing says, “You all better shut up.” But by now we’re out of control, rollin’ on the floor. Out of nowhere, like The Incredible Hulk, Uncle Lawrence appears in the doorway. “I’m going to say this, one time. Go. To. Sleep.”

I’m still not sure if Jimmy Lamar’s been to Etta’s or not. The way they tell stories in Mississippi—you believe it, even when they’re making it up.

* * *

I’ll tell the truth. I don’t like church in Detroit. Sometimes, it doesn’t make a bit of sense—starting with The Commandments. Does the guy who covets his neighbor’s wife really go to the same hell as the Boston Strangler? Annette Funicello? If covet means what I think, I’m doomed already.

But Sunday morning in Mississippi means Mercy Seat. And Papu, the Reverend Jordan, is preaching.

The choir marches in to “How I Got Over.” People are clapping—some right on the beat, others are doing this in-between, double-time thing. It’s on.

The assistant pastor runs through the list of the sick and shut-in and reminds everyone that, just as man does not live by bread alone, neither does the church. They pass the collection plate. Then it’s time for the sermon.

Papu starts off like a schoolteacher, calm.

“In Genesis, Chapter 2, Verse 7, it is written. ‘And God, formed man out of the clay.’ ”

He speaks slowly.

“Our topic this morning is, A Man is Made of Clay.”

Papu takes his time to make sure everyone understands.

“This is God’s way of reminding us. That we are of nature.”

A voice from the back of the Church: “Tell your story, Reverend.” He keeps going, just a little faster,

“God is in every natural thing. He’s in the beams of sunlight that stream through that window on Sunday Morning. He’s in the showers of rain that water the fields. And, he’s in that clay from which we are made.”

From the choir loft, a short, sharp, “Yessir!” Papu’s on his game this morning.

“Now there are people who say you’ve got to take the bible literally—every word. Chapter and verse.”

“That’s right, Reverend Jordan.”

“Well, I think God expects us to read The Word.”

He pauses.

“And, See, . . .The meaning behind it.”

A low rumble, Hmmmm, from the deacons’ bench. Then, Papu, with a teacher’s tone,

“We are clay. Life molds us.”

“Yessir.”

“We are molded by the things we love . . .

And, by hate.”

By now the whole church is on it—singing, moaning, chanting hallelujahs back at Papu. Even I feel an “Amen” coming on. Before a shout could leave my mouth something says, “Do you really want to be the kid from up-north who messed up the Reverend’s rhythm?” That must have been Jesus looking out for me.

Papu continues,

“You can see it in a child as he returns his mother’s smile.”

“Preach the gospel, Elder.”

“Molded by the things we love.”

Chords float from the piano.

“And . . . By hate.”

Now, Papu goes to work—each line higher, faster. Every call-back stronger, louder.

“The flatlands and the hills of Mississippi are stained . . . and the backwaters run red with blood.”

Shouts. From every corner of the church.

“These are difficult times . . .”

“They Hard, Reverend. They hard”

“And this is a difficult task.”

“Yes it is, doctor.”

“It’s human nature to be drawn to good . . . and to evil.

And, we are human.”

“Tell the truth!”

“But, in this life.”

“Yessir!”

“You’ve got to decide.”

“Preach Reverend!”

Then Papu, that 80-year-old man, leaps straight up into the air and lands like thunder with,

“Who you’re gonna be!”

He comes down pounding the bible so hard with his fist that the pulpit shakes.

I jump, the same as I do at a scary movie, and almost fall out of the pew. The good sisters, eyes closed, hands raised, grasp the air, like the hand of Jesus is just beyond their fingertips. Others just shake their fans faster and wipe the sweat from their foreheads. The nurses in white uniforms stand there, ready, just in case the Holy Ghost gets ahold of somebody. I elbow Margaret. “This is church, for real.” Mamoo is quick. “No talking. We’re in the SANCTUARY.”

The air fills with God a Mighty, Lawd a Mercy and Sweet Jesus.

Papu’s calmer now.

“We are clay. Don’t let hate shape you.”

The piano swells.

“Don’t let their hate shape you.”

The choir picks up the beat from the piano’s bass notes. They file out of the loft, and two-step down the aisle to “Pass Me Not O Gentle Savior.” For a minute, I forget about the devil’s music.

* * *

It’s morning at Mamoo and Papu’s house. With so many kids around I don’t expect Mamoo to even know which one I am. But she remembers I am the Bug Man and has a big Kool-Aid container, a makeshift bug house, ready for me.

I poke around for bugs in the tall grass out past the pecan trees. Aunt Leona thinks she’s too far away for me to hear her tell cousin Bessie, “You want to know about men? Just watch a boy and a stick.” Down here everybody’s like the guys in the broadcast booth. They comment on every move you make. I need to put some distance between me and the play-by-play crew.

So, I tell my gramps that the really good bugs must be in the woods. “Right?” Uncle Carl jumps in “Somebody needs to tell that boy about the woods. You know what happened . . .” Papu, shuts him down with a look, and just tells me, “It’s best to stay around here. There are plenty of ‘em out in the yard.” He is right. Next thing I know, I’ve got the biggest spider I’ve ever seen in my bug house. Bees and dragonflies everywhere. By the way, doing the actual thing really is better that just thinking about it beforehand.

Mamoo calls out the window, “Enough with the bugs. Old man! Bring that young man in here. I want to see everybody at my table in fifteen minutes.”

I stash the bugs outside and dive onto the living room couch with my notebook. Just killing time before lunch. I start to write. Papu finishes a call and hangs up the phone.

I like hanging with Papu. What we talk about is always just between us. He asks, “How do you like being back in Mississippi?” The thought of it puts a smile on my face, “Love every minute of it, Papu.” Then I stop, “Except . . . to tell you the truth, I’m starting to think there’s something wrong with white people.” Papu laughs. But I’m not joking. “I don’t think white people down here will ever change.”

But all Papu says is, “Have faith.”

I really didn’t want any more of that. I’m not sure if I should say it, but I do. “Yeah. I hear all of that in church. But the things I see in the regular world—I, I don’t know.”

Papu looks over my shoulder. “They tell me you make music.” I laugh. “We just play around with it.” He continues, “I see you carrying that notebook. Everywhere.” Papu has that patient sound. “When you look at that blank page,” he pauses “You know it will fill with words; you know that out of the silence will come a song. That’s faith. You’re going to need that in life.”

Jimmy Lamar’s in the doorway, “Yeah. Faith. And a righteous left hook. That cracker knew he was about to play Max Schmeling to Unko Jim’s fist.”

Papu stops him. “You know I’m a minister of the gospel. I can’t condone threats of violence.” He rubs his whiskers. “But I will say, I think Jesus would forgive.”

All of the sudden somebody screams. Then again, louder, “Oh God. No. God No. God No. Come in here. Quick.” We crowd around the television in the den. They had interrupted the broadcast for a special report. A helicopter circles as they pull a burned-out car from a muddy creek. White men wearing cowboy hats and holsters watch from the water’s edge. Pops glares at the screen. Girl cousins turn away and bury their faces in mom.

The days zip past and our trip is coming to an end. The last night of vacation, I get to ride along with my cousins Jimmy Lamar and Coela on a trip to Jackson. Now, I know what the grownups were talking about the night we got there. The three young men in Neshoba County were the civil rights workers who had disappeared. Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Mickey Schwerner.

On the ride, the talk about civil rights workers lasts all of two minutes. I’m not sure if my cousins don’t want us to get any more spooked about Mississippi, or if they’re trying not to spook themselves.

In the long silence, I think about Brownsville. Now I know what Pops knew when he took on the gas attendant. I’m even more proud.

It’s a night drive out of the delta down Highway 49. Taillights in the distance disappear over a hill and reappear as they climb the next one. I imagine invisible things in the night woods. I imagine a carload of men rising up in the rearview mirror. I imagine our family in Greenville, on the porch, waiting all night for news that we’re safe. But I stop—can’t think bad things before they happen, unless you want to live it twice.

I’m usually pretty quick to see what’s going on. But it took a wild-eyed man at a gas station in Brownsville Tennessee for me to start to understand all of this. On our other summer vacations we swam in the pool under a sign that said “Colored Only” and followed our cousins and the arrow that points Negroes to the balcony at the movies. Now I get it. For some people, we’re like when you touch something nasty and have to wash it off.

I wonder, is Sandy Koufax like that, too? Nah, he’s cool. You can tell just by the way he is. But I wonder who is and who isn’t like that. The men at the river wore cowboy hats. White people can sound so nice, even polite. They’re not like bees. You can’t tell who they are by how they sound. You just don’t know what they’re thinking.

We pile into the car for the trip back. It seems twice as long. We mostly talk in the back seat. No singing. Now we have stories to bring to our friends in Detroit. I can’t wait to show off my bug collection. I could brag about my dad. But if I tell the truth it’ll sound like I’m making it up. Gonna tell it anyway.

We’re going to have to figure out some way to explain all the signs telling people to go here, not there, don’t do this or turn back, you’re in the wrong place. We can’t leave out the one sign that made me and Margaret crack up, the one where the person who made the sign couldn’t spell colored. It’s our job to find the words they should have used, even in Mississippi.

Epilogue

In 1982, when I was young lawyer and activist, I was introduced to novelist James Baldwin as someone he should get to know. Arrangements were made for us to meet on a Sunday night over dinner at the Ginger Man on West 64th Street in New York. With a head full of ideas and a youthful lack of the good sense that leads one to yield the floor to superior brilliance, I seized on his use of the term Jim Crow. I suggested that words like Jim Crow and segregation were polite euphemisms that diminished and even camouflaged the true nature of the black experience in America. I lucked out. He dived in.

We talked about the power of naming things and how what we decide to call something shapes how we think about it. We talked about the divergent American experience, the parallel universes of black and white, how thousands of black families had been refugees from America, seeking sanctuary in Canada. We spoke of how the woods, the idyllic sanctuary of Thoreau and Emerson, meant something very different to black men of my grandfather’s generation. There were Hellhounds on Robert Johnson’s trail. In Papu’s lifetime more than four thousand black men were lynched. Their remains were just part of what you expect in the southern woods, and backwaters. Baldwin recited lines from Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.” I recited Papu.

Papu knew the Bug Man was better off in the high grass near the house. A few years ago down the road in a town called Money, 14-year-old Chicago schoolboy Emmett Till’s summer vacation ended when he was abducted and murdered after he smiled at a white woman.

Baldwin spoke of Freedom Summer as the philosopher poet of the civil rights movement. I shared my memories of that summer as the child of two great black migrations—the Underground Railroad to Canada, and the post-war flight from the south to the urban north. My Freedom Summer, with a seat at the window of history.

Baldwin’s reference to his friends Martin, Medgar and Malcolm was my cue to speak less. Good thing. Baldwin, like a horn player, strung together lines about men like my father who fought wars on two fronts—in the Pacific and then at home. He marveled at the many acts of everyday heroism and lamented that they might be lost to history.

Baldwin reminisced about the ruckus he and Nina Simone caused when they loudly sang “Mississippi Goddamn” in a restaurant. We laughed and did a short reprise for Nina as our waiter walked us to the door. Baldwin’s last words that night: “Promise me you’ll write that story.”

So I write for my father, my mother, my grandparents, and for James Baldwin.

After 66 years of marriage, Jim Jordan still winks at Ilene and can give you The Look, if you step out of line. And Ilene Jordan still carries herself as if she’s about to receive her statue. To this day, no song is safe in Jordan hands.

Herb Jordan is an award-winning author and commentator on American culture. He taught at the University of Michigan Law School where he received the L. Hart Wright Outstanding Faculty Member Award. His essays include “Motown in Love” (Random House), featured on NPR, and “An Elegant Equation” (Universal). Jordan has composed for Count Basie and produced the 2005 Grammy nominated album American Song by Andy Bey. Jordan is currently developing “A Seat at The Window” as a feature film.

Half a Mile From Heaven: The Love Songs of Motown

Detroit in the 1960s was an unlikely stage for a production that featured some of the most inspirational love songs ever written. It may seem equally unlikely that most of those songs were written by young black men. Default notions of romance are an awkward overlay to the reality of this city of steel and sweat, Joe Louis and Jimmy Hoffa. Rough? Tanks that rolled off Detroit’s assembly lines and onto Europe’s beaches as liberators returned home twenty years later to quell urban rebellion. But there was no simple way to quiet the musical movement that was surging in the basements and on the street corners of Detroit’s black neighborhoods.

The city vibrated. Every block had a band, it seemed, and on summer nights young men harmonized under the streetlights. Mixed in with homegrown versions of hits by Ben E. King and the Moonglows were original songs penned by the neighborhood tunesmith. Sunday morning you had to arrive early to get a seat at church. Overcome with the spirit, preachers resorted to singing their sermons. At New Bethel Baptist Church you didn’t mind standing for two hours if you could hear the Franklin sisters—Aretha, Carolyn, and Erma- sing “How I Got Over.”

But there was a new sound. As word spread through the neighbor- hood, teenagers scrambled, high-top shoes and bicycles, to the parking lot of the Bi-Lo Supermarket where on a makeshift stage twelve-year-old Stevie Wonder performed “Fingertips.” Before long, record store clerks were inundated with customers describing, and sometimes attempting to sing, a few bars of the sound they heard on their transistor radios.

These were the 1960s, and poverty, segregation, Vietnam, and nuclear gamesmanship convened in a funnel cloud that threatened to rip through the American fabric. But with the innocence of a first kiss, the poets of Motown conjured up a black Camelot and took America “up the ladder to the roof” for a view of heaven. From rooftops to blue-lit basements they danced, black and white, fast and slow, as young men testified that they would “find that girl if [they] had to hitch hike ’round the world,” and women replied, “ain’t no mountain high enough to keep me from getting to you.” Boys in the ’hood—long typecast as the least productive, most destructive element of society—wrote knowingly and elegantly of life and love. The young women dazzled with a mix of soul and social graces, grace they maintained even when on Southern highways gunshots were directed at the Motown tour bus.

The thought of white teenagers falling under the spell of black music mobilized the guardians of white culture. Everyone knew the invisible perimeter that insulated white America would soon be irreparably breached. The usual operatives took measures to thwart it. Music was on the front lines of the battle. In retrospect, the lastgasp efforts at interdiction seem comical. A now infamous poster that circulated throughout the South warned white parents not to allow their children to listen to Negro music, lest they end up with one on the dance floor or otherwise.

As great as Motown’s records were, the company’s executives knew the power of live performance. The Motown Revue featured almost the entire roster of artists and a live stage band. The artists were confronted for the first time with overt segregation when the caravan rolled into Southern towns. Neighborhoods in Detroit were neatly divided along racial lines, but in the South the lines were often drawn with firearms. What was taken for granted in Northern cities could be a perilous undertaking in the South. Bobby Rogers of the Miracles recalls that a gas station owner confronted him with a gun after he used a white restroom. White and black teenagers were typically assigned to opposite sides of auditoriums in Southern venues. But on many occasions the police were powerless to enforce the separation as the teenagers, in their own version of a freedom march, just stepped to the beat.

In the mid-1950s television sponsors squirmed at the thought of having their products associated with Nat “King” Cole’s variety show; in the absence of commercial support, the show quickly vanished from the air. But by the early 1960s, families gathered on Sunday evenings to watch Ed Sullivan introduce the latest Motown sensation. Disc jockeys thought nothing of sandwiching a Rolling Stones track between hits by Martha and the Vandellas and the Four Tops. The seeds of this social revolution were scattered on the winds of radio and television airwaves. While activists preached and lawyers agitated, Motown crept into white homes, Southern and suburban, through Radio Free America. Once the Marvin Gaye poster went up, there was no turning back. White girls swooned over Marvin as had their mothers for Frank Sinatra. Even in the heartland, white boys earnestly attempted Motown dance routines and, for a moment, imagined that they were black.

The specter that this music might incite race mixing was rivaled only by the fear of images of black romance. The myth ran deep that among blacks love was characterized more by physical urges than by the complex universe of emotion that transcends motor response. Thomas Jefferson could have been a Hollywood studio executive when he dismissed sentiment among blacks as “less felt and sooner forgotten.” If you didn’t see Porgy and Bess, Carmen Jones, or Paris Blues, you might have missed Hollywood’s entire pre-Motown output of film portrayals of black romance. In the age before videotape, DVDs, and cable, most people, black and white, had never seen affection expressed between blacks in film or on television. While major studios ignored black love affairs, the Motown songwriters understood the poetry of Everyman. These songs explored romance’s jagged landscape—infatuation, discovery, love’s grip, love lost. They told of brokenhearted men and wrote of women who know “how sweet it is.”

A sign over the door of the house on Detroit’s West Grand Boulevard read Hitsville USA, a slick slogan worthy of the other major presence a half mile down the boulevard, General Motors. Motown’s eagerness to market its own assembly line obscured for some what really went on inside that house. Close observers watched the parade of odd-shaped instrument cases that concealed everything from bongos to bassoons and the procession of young men with skinny ties,cropped hair, and satchels stuffed with staff paper. They were the ones who knew the secret language of song. It was a production line but one that dispensed magic. Names such as Ivy Jo Hunter, Sylvia Moy, Hank Cosby, and Clarence Paul were scarcely noticed by a public in love with the flourish of sequined stars. The songwriters, invisible architects of the Motown sound, assembled the substance of everyday into songs that were at once sophisticated and earthy, personal and universal. In many ways, it was the Great American Songbook of the second half of the century.

Fans may have believed that Diana Ross wrote “You Can’t Hurry Love.” She was convincing. The truth is, before a song reached the artist a songwriter or two had labored over the turn of a phrase, reshaping it until its internal rhythm and contours fit the music like counterpoint.

Not long after the spark of an idea had blossomed into a song, it was thrust into the glare of the Hitsville proving ground. Each song had to run the gauntlet of rival songwriters, producers, and the man who started it all: Mr. Gordy, who himself had written a string of hits. Berry Gordy instinctively knew that great music is built from the song up. Songs were placed on trial and any facet, from the euphonics of the words to chord structure, was fair game. Morris Broadnax who, with a teenage Stevie Wonder and Clarence Paul, wrote the masterwork “Until You Come Back to Me,” recalls that “new songs were worked on between Tuesday and Thursday, and on Friday all the songwriters presented their best material to the staff. There was so much great music that you hoped that yours was one of the few chosen on Monday.” Collaboration and competition sharpened the writing. Smokey Robinson, Holland-Dozier-Holland, Ashford and Simpson, Strong and Whitfield, and Stevie Wonder would arrive on Fridays and place their latest in the hands of musicians James Jamerson, Benny Benjamin, Robert White, and Earl Van Dyke—the Funk Brothers. Cutting sessions jazz musicians’ venerable device for raising the creative bar found a home in the basement of Hitsville. It was hand-to-hand musical combat and whoever was left standing made a record.

Love has long been a staple in the American song tradition. Black songwriters have always created the template for jazz and blues, and W. C. Handy and Duke Ellington knew their way around a love song. But beginning in the 1930s, black artists often looked to Jewish songwriters for a seemingly endless string of pop hits. Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, and George and Ira Gershwin lined the pages of the American songbook with interpretations by the great black singers. The combination was potent. Imagine American song in the absence of Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong’s “Cheek to Cheek” duet or Sarah Vaughan’s “April in Paris.” This brilliant symbiosis continued in the late ’50s and early ’60s as black popular artists turned to writers such as Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, and Carole King and Gerry Goffin for songs like “Stand by Me” and “Will You Love Me Tomorrow.” But Motown from the musicians and singers to the producers and songwriters was a community project. While everyone was invited to the party, this music was a product of the tough public housing projects and Detroit’s strong black middle class neighborhoods of neatly cropped lawns, family dinners, and traditions that went back generations. The accumulated musical knowledge of neighborhood masters was summoned. The call went out to poets, arrangers, practitioners of jazz and gospel, and the classically trained to form what writer and producer Clay McMurray describes as a Noah’s Ark of talent. The studio was said to have been open twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

In the 1960s the times they were a-changin’. Songwriters drew their inspiration from issues of the day. Artists believed in the power of music, that they could change the world with a song. The ’60s manifesto assured us that “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “We Shall Overcome” could end the war and make the walls of segregation “come tumblin’ down.” Singer-songwriters chronicled the unfolding social drama, and when they spoke of love it was in the most personal way. Detached, formulaic love songs now seemed anemic, as Bob Dylan and the Beatles redefined the subject matter of popular music. For a love song to grab hold of this generation something different was required.

The Motown writers responded with songs that transformed the prosaic into the poetic. The girl down the block became a goddess, and the path to her heart, an epic journey. From “Bernadette”:

And when I speak of you, I see envy in other men’s eyes,

and I’m well aware of what’s on their minds.

They pretend to be my friend, when all the time

They long to persuade you from my side.

They’d give the world and all they own

For just one moment we have known.

The Motown roster of artists was packed with female vocalists. Men wrote for Mary Wells, the Supremes, the Marvelettes, Martha and the Vandellas, and every other woman on the label. Sylvia Moy’s early compositions—“I Was Made to Love Her,” “It Takes Two,” “My Cherie Amour” did much to establish a standard of idealized romance. To write effectively for female vocalists, the male songwriters were forced to immerse themselves in a woman’s point of view. Women wait for, agonize over, and celebrate love when it finally arrives. The male songwriters rejected Pavlovian swagger; like Marco Polo bearing gifts from a strange land, they delivered to the male vocalists the textures of romance. Gone was the supposed indifference to the joy and pain of love. These writers discovered love as a force of nature, a celestial presence around which pride, reputation, and the grab bag of male defense mechanisms simply orbited. But this was no weak, victim-of-love routine. The men sang songs infused with unmistakable ardor and palpable virility and with the sort of strength that flows from the yin and yang of love. “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” laments, “I know you want to leave me,” and then stiffens, “but I refuse to let you go.” Marvin implored, “Let’s get it on,” but assured “I won’t push you, baby.” When the men expressed overblown confidence, it was as a foil for the failure to win the love of a woman. “Can’t Get Next to You”: “I can live forever if I so desire . . . I can make the grayest sky blue . . . But I can’t get next to you.”

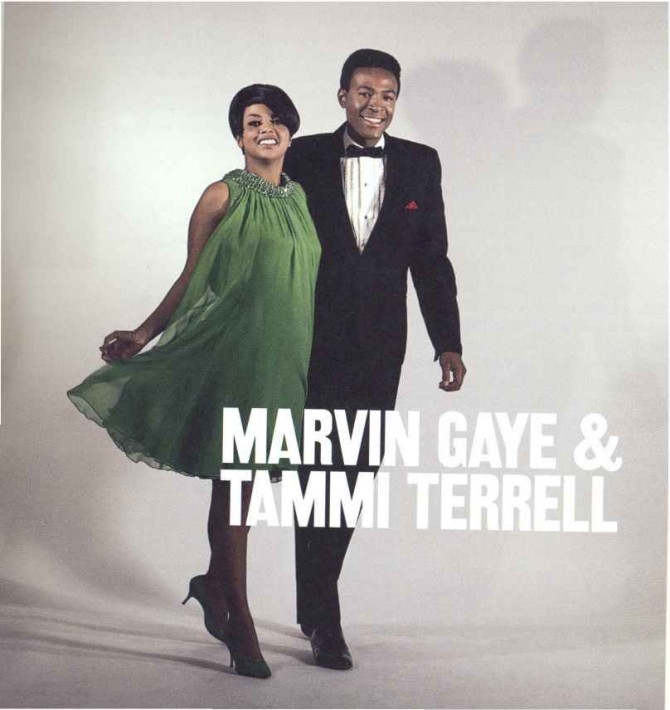

These were strong men who understood the power of love and women’s power in love. Grown men dropped to their knees on stage and wished it would rain. It was this willingness to pierce the façade of male invulnerability that endeared Motown to anyone who had a heart. Smokey: “So, take a good look at my face. / You’ll see my smile looks out of place. / If you look closer, it’s easy to trace / The tracks of my tears.” When it happened, love was strong, supportive, and reciprocal. Lyricist Nick Ashford, as sung by Marvin Gaye to Tammi Terrell: “Like an eagle protects his nest, / for you I’ll do my best, / Stand by you like a tree, / And dare anybody to try and move me.”

The best of Motown navigates the narrow passage between sophisticated linguistic expression and popular tastes, one obscure metaphor too many, and the audience vanishes. Popular music, by definition, speaks the common tongue. But an overdose of cliché guarantees a song will not survive beyond the moment. Like Billy Strayhorn and Lorenz Hart, the writers of Motown knew that a well timed intelligent phrase was the soul of cool. It was sexy as hell. It played both in the housing projects and in Peoria: “I did you wrong. / My heart went out to play. / But in the game I lost you. / What a price to pay.”

This was soul music, sensual and sweet and unafraid to display its affection publicly. Much of it may have been created in the midst of the bare-knuckles brawl that was, and is, urban life, but the music transcended bitterness in favor of life-affirming dignity. Barrett Strong, who cowrote, among others, “Just My Imagination” and “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” cites “real life” as his inspiration: “Most of us came from homes where there was a sense of family and optimism.” There was always the whispering sage. Mama said, “You can’t hurry love” and “You better shop around.” The songs were girded by an African American ethic of grace in romance: Beauty’s only skin deep, wait patiently for the real thing.

America was enchanted. The Supremes graced the cover of Time magazine. When the Motown tours went international, European teenagers, who had learned English by singing along with the records, enthusiastically delivered background vocals from the audience. Musical artists from every quarter spoke of Motown with admiration bordering on reverence. The Beatles, Laura Nyro, and James Taylor, master songwriters themselves, recorded Motown songs. Bob Dylan spoke of Smokey Robinson as “the greatest living American poet.” Singer-songwriter Jackson Browne compared the songs to the era’s engineering marvels produced in Detroit’s auto plants. Indeed, the best Motown songs are masterpieces of design. Like Oscar Hammerstein and Cole Porter, these songwriters could tell a story in Technicolor. You were given a private tour of the “seven rooms of gloom,” invited to “walk the land of broken dreams,” huddle “in the shadows of love,” or were shown “a green oasis where there’s only sand.” The songs were often Greek drama in miniature; you understood what a mess the singer was in, but you also knew he caused it. Hubris was inevitably followed by some humbling comeuppance. Men who thought they had a woman dangling on a string were beaten to the punch and dismissed. Hunters were captured by the game.

In the 1950s, three chords ruled pop music, but these writers served up a Crayola box of harmonic colors. Songs such as “For Once in My Life,” “Reflections,” and “You’re All I Need to Get By” displayed a broad harmonic vocabulary without an air of pretension like the guy who can walk into a barbershop, use words like pedantic, and still be one of the fellas. Products of the Detroit public schools’ then legendary music program and neighborhood joints that still featured live jazz, the Motown songwriters knew song struc- ture from way back. They could back cycle, dangle a plagal cadence, modulate, and flash a little chromaticism without breaking a sweat. When only two chords were needed to get the job done, they could weld C-sharp and F-sharp together so tightly they flowed with the inevitability of night into day. It sounded as if they were the first to discover a simple triad. The Motown songwriters instinctively understood the irreducible principle of writing anything: have something to say, say it, and stop. These writers delivered concise points of view, equal parts declarative and metaphorical: The average length of a Motown hit song between 1963 and 1968 is less than three minutes. The ghetto Zen masters set out the rules of love from the practical to the ethereal as if under the watchful eye of the haiku police. You were advised to ignore friends’ advice if love hung in the balance, reassured that pretty girls were a dime a dozen, and emboldened that with a true heart you could still win the girl even if you didn’t have a dime.

The musicians, not technically composers, contributed themes that became inseparable from the songs themselves. They echoed the lyrics with uncanny wordless precision. James Jamerson strung together bass lines of Morse code; you could hear Mama’s relentless “Love don’t come easy, / it’s a game of give and take. ” William “Benny” Benjamin introduced tunes with signature drum lines you couldn’t imagine the song without. Even the baritone saxophone, a Snuffleupagus of an instrument, sounded hip. These musicians could have gotten people up on the dance floor with a chorus of tubas.

Through the funk, innocence percolated to the surface with bird- like girl singers and the nimble percussion of pizzicato. There were finger snaps against a backdrop of symphony strings. This was music full with anticipation. The days had faded when bluesmen painted the Delta with hard times and hellhounds. These were the ’60s. There was talk of living where you wanted, getting jobs because you were qualified, and looking a white man in the eye without risking your life. Mr. Gordy owned the record company. Integration was one thing, freedom was another. When in 1964, Sam Cooke sang “Change Is Gonna Come” on the Tonight Show, it sounded like the words of a prophet.

As early as the mid 1950s, the nation’s vast educational resources had begun to trickle into previously neglected neighborhoods. Smokey Robinson traces his interest in language and composition to the Young Writers’ Club, an after-school workshop convened by Ms. Harris, a visionary elementary school teacher. By the 1960s, a belief and investment in the untapped resources of marginalized Americans was becoming an article of faith.

Programs from Leonard Bernstein’s Young Peoples’ Concerts to Head Start recognized that by denying opportunity to these communities the nation had robbed itself of untold contributions in science, art, and culture. The concept of a Great Society gained currency. On the neighborhood level, the Detroit public schools taught music theory, composition, and performance as if they mattered. The pace of social change was accelerated in the 1960s. What had been incremental and generational now arrived in clusters. In January of 1963, as Motown began to dominate the pop charts, a sixteen-year-old André Watts, substituting for an ailing Glenn Gould, walked onto the stage at Lincoln Center and delivered, note perfect, Liszt’s E-flat Concerto. In 1964, as Motown’s grip on the charts tightened, a fresh-faced Cassius Clay thanked America to refer to him henceforth as Muhammad Ali. Berry Gordy brought composers, lyricists, singers, and musicians together with his own defiant gospel of optimism and a belief that with opportunity and a forum for expression there were no limits to what could be accomplished. Their music was part flower-pushing- through-cracks in the concrete and part root shattering it.

The fleeting age of innocence and hope gave way to summers of discontent, and in an act of collective self-immolation black neigh- borhoods from Watts to Detroit were consumed in flame. A series of events conspired to dismantle the delicate, cautiously entertained aspirations. The descent was punctuated by the assassination of the messengers of change: Malcolm X, John and Robert Kennedy, and Medgar Evers. With the election of Richard Nixon by a silent majority that dismissed social programs as the product of a bleeding heart, reality fell far short of the vision. Hope withered. But for a time the sense of optimism in music held fast. Then, on a spring morning in 1968, word came from Memphis that Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot. The blues were back. As in the old Ellington hook, black America struggled to keep the song from going out of its heart. Within black songwriting the battle had begun between romance and rump shaking. Defeatism is anathema to art. After what happened to Martin, it seemed that only a fool could believe.

Within months of the King assassination, the Temptations’ “Cloud Nine” stripped the veneer of hope and exposed a reality that could be tolerated only through a cloud of marijuana smoke. This moment was more about raw reality than idealized love. From “Ball of Confusion” to “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone” and “Run Away Child (Running Wild),” the promise of a black Camelot settled into sullen defiance. When it came to love, male vulnerability was no longer an option. In “Uptight (Everything’s Alright),” Stevie Wonder once bragged that he was the apple of his girl’s eye, even though the only shirt he owned was hangin’ on his back. Soon a caricature of masculinity would dominate black music. Why contemplate the way to a woman’s heart when you could dazzle her with your jewelry, a blocklong car, and a wad of cash? In the coming decades, music education was phased out of many of the public schools. Those with talent learned to use turntables to scratch out a new beat. Seduced by the illusion of props, a new generation of writers confused bluster with strength and manhood with an impenetrable heart. Smokey Robinson wrote of love for a woman as “a rosebud blooming in the warmth of the summer sun. ” But as the African American tradition of romance faded from the music, a woman was more likely to be reduced to her anatomical components.

Still, the legacy of discipline and creative inspiration that defined the early days of Motown is manifest on Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On and in a series of albums by Stevie Wonder culminating in Songs in the Key of Life. The teenage apostles of boy-girl love became standard-bearers of a spiritual, universal love. For them, soul music had evolved into music of the soul. Their lyrics have become sacred text: “War is not the answer, for only love can conquer hate,” “Love’s in need of love today.” As did John Lennon with “Imagine” and John Coltrane with A Love Supreme, they looked beyond the personal and dreamed.

A Stevie Wonder lyric lamented that love had taken flight “and then a half a mile from heaven” dropped him back to this cold world. Motown’s songs of romance ascended with the promise of change and faded with the onset of cynicism. In the process, the music was itself transformative, inspiring a community defined not by geography, class, or race but by a sense of common experience. The gospel of change that ignited the love affair in black music may have diminished, but for an incandescent moment, Motown celebrated life and love. No one who hears it will ever forget.

Copyright 2006 Herb Jordan

An Elegant Equation by Herb Jordan (from the Motown Singles 1967 Box Set)

.